How a paradigm shift will influence the cost of Dutch Mental Health Care

Gert Jan de Vries, MSc

Talk delivered at the International Conference on Transdiagnostic Approaches to Mental Health in Cambridge, UK, September 2023. Based on a Clinical Psychology Masters’ thesis at the Open Universiteit, Nederland.

How does an aspirine know where the pain is? That’s the title of a book full of fun medical facts. In my view it’s also a metaphor for psychotherapy. How does a therapist know where the mental pain is? And if she does, how does she cure the disease, how does she flip the internal switch of the client? You know that famous switch on the inside where her hands cannot reach? For that, in my estimation is the main unanswered question in psychotherapy: what constitutes change? And to broaden the metaphor: Eventually, in the book the question about aspirine is not answered.

What I’m about to tell you is a summary of my master’s thesis in psychology, written in 2021 and 2022. It contains a plea for a paradigm shift towards transdiagnostic methods that will annually save billions we spend on mental health care. I will illustrate this with a brief history of recent – and quite unproductive – changes in the Dutch health care system. We have lost nearly two decades of old school marketplace fundamentalism and it’s time we started doing better.

I think this is all quite a statement for someone who only recently studied psychology, so it’s maybe time to briefly introduce myself. For over 30 years I have worked in publishing after having written my PhD in literature in the early 1990s. I have edited, written, cowritten, translated and reviewed many hundreds of books, from science to porn and from hermetic poetry to popular non-fiction. During this whole period, I have been married to professional psychologists – two -, the first being a scientist trying to improve Leary’s rose, the second a practitioner, whom I helped setting up a private practice that focusses on schooling future psychotherapists. So, I’m not a complete novice.

A brief history lesson

The neoliberal revolution of Thatcher and Reagan took power away from national institutions and handed it over to the free market, with one central message: the market place is always right. Dutch politics also liberalized many national institutions, with health care as last in line. Until then we had a communal system of health care, not unlike the NHS, including some Bapu-like private parties on the side.

In 2006 health care got commercialized. Business advisers took the reigns, insurance companies started telling doctors what to do and although GPs went on strike for the first time in history, the old system was transformed beyond recognition.

Software systems were implemented, but they weren’t built upon quite recent insights like those of the Transdiagnostic community, but on the reductionist logic of the DSM, the most researched and thus most Evidence Based system to date. This practical – if not opportunistic – choice by the software makers had huge implications. The already existing doubts among practitioners about the applicability of DSM were silently swept under the rug and as a result the internal discussion between practitioners and theorists seemed stifled.

One novel feat of the new system was that mental and somatic health care were put into one system, as equals. Every hour of therapy, letter to a GP and psychodiagnostic report written became a billable action like they were bandages applied, injections given, or hips replaced. Every patient or client got a DBC – a diagnose-treatment-combination, an administrative slot in which all treatment activities were filed. Everything DSM based of course.

And so, the pinnacle of reductionism was reached: a unique diagnosis and ditto treatment for every patient, completely administrated and communicated between many institutions in such a coded way that the patient’s privacy is guaranteed, with files being stored for at least two decades. From a Transdiagnostic stance all this reductionism was incredibly inefficient because it was so unnecessarily time consuming. And imagine how intrusive all the questioning was – and still is -, and how unsafe all this storage is in a world where within a few years AI will crack any digital lock in milliseconds.

As predicted, none of the targets of this huge operation were met. The budget went up to well over 4 billion euros, instead of down, as did the price per treated patient. The number of treated people in the meantime went down while waiting lists grew to unacceptable lengths. By now well waiting lists are unacceptably long. I recently heard someone complain she had to wait for two years for an intake!

In the meantime, psychology students have an increasingly hard time getting an internship, norms for professionalization are upgraded all the time, and practitioners are complaining about spending 40+% of their time administrating.

So, in short, health care became a bureaucracy with unworkable professional standards and basically the system went broke.

Behind the scenes, inside the therapist’s office

DSM logic and a system of convergence (thank you, Pauline Tieleman, for the term) were clearly no effective way to organize mental health care, but what was? Well, for one thing, the internal discussion between practitioners and theorists hadn’t been stifled at all. Practitioners in large numbers left the strict DSM-logic for the much more insightful and practical Transdiagnostic approaches. They creatively administrated them in the DSM based insurance systems.

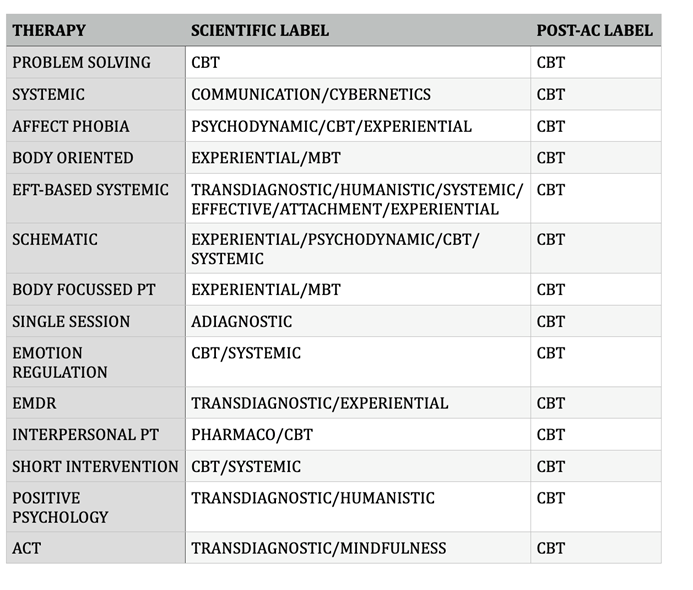

Even postdoctoral schools labelled every Transdiagnostic approach ‘CBT’, when many of them would probably be better categorized with terms like holistic, because they were focused on way more mental health aspects than the reductionistic DSM. Still even the term Transdiagnostic relates to DSM – because you can only be trans-something when you recognize the existence of that something. I therefore assume that the term ‘third generation CBT’ was a ploy, a kind of mimicry. If so, well done, my Transdiagnostic friends!

All in all, while discussions about diagnoses, EBP and billability etc. went on above board, below board treatment methods evolved.

In 2017 our national budget office concluded the system didn’t work properly. A few years later the even keel treatment of somatic and mental health care was partly abandoned and in 2022 new rules were implemented for billing mental health: the Care Performance Model or ZPM. In this instance the scientific council for government policy stressed forcefully that EBP (read DSM) must be retained.

Having worked with this new ZPM-system for a little over a year, I must say it doesn’t fulfill its promises. It still uses DSM-codes but also gives room for personal judgement. It’s more complicated than before, it often provides ambiguous information and in my humble opinion it generates more administrative work instead of less.

Change of paradigm

Therefor the better option probably would have been divergence instead of convergence (thanks again Pauline). That means a common starting point for treatment instead of loads of analyses beforehand and a lot of negotiating with clients about treatment goals and means. Divergence in this case also implies putting the patient to work instead of the practitioner. Haven’t we known for decades that the client is the main factor in every treatment, the “dependent variable”? Haven’t we also known for decades that the influence of the therapist is limited, considering that even self-help books have been proven successful? So, this medical model of mental health care we are in general still upholding isn’t just artificial and ineffective, it is basically incorrect. The therapist cannot change the client’s behavior or thoughts, however brilliant the diagnosis. She can at best help the client achieve change. For if there is a switch to be flipped, the client is the one to do it. Luckily recent international developments show more attention for the patient side of mental health care: not ‘how sick does the doctor think you are?’, but ‘how sick do you feel?’

By changing the way we look at mental illness and therapy we are changing mental health care itself. We start to see that the aspirine and the therapist don’t know where the pain is. I firmly believe that we need to stop this medical model to get to a more effective and humanistic mental health care. That’s not what Neo-liberalism brought us. In fact, Neo-liberalism eclipsed the evolution of mental health care, which around the late seventies was just starting to ‘get it.’

At this point in my master’s thesis, I jump back into time to the 1970’s, when behaviorism was under scrutiny and several kinds of alternatives were getting into the spotlight. Since my time on this stage is limited, I must make a shortcut here to one of the alternatives of those days that was largely overlooked.

It’s called Perceptual Control Theory or PCT, invented and constructed by William Powers, a medical engineer and psychologist. PCT is a very broad theory that has since been applied in all kinds of disciplines, from cybernetics to machine building, from robotics to philosophy.

PCT proclaims that we are very efficiently organized control systems. With everything we do, we spend the least possible amount of energy, in accordance with the evolution theory. In order to do this, we control our actions by what Powers called a perceptual hierarchy, a system which basically helps us decide at which level to act.

My tea is cold by now. That helps illustrate PCT. I take a sip and put my cup down. Then I take another sip. Now can I see a show of hands: did I do the same thing twice?

And another show of hands: did I do two different things?

Those who think I did the same thing twice are basically Cartesians. You believe that the same instruction or stimulus leads to the same action or result. That, in principle, is the idea behind Behaviorism and CBT, which Powers ridiculed in the first chapter of his book. It simply can’t be right, because if I lifted the cup the second time with the same power and speed of the first time, it would have ended up higher than my mouth, for it contained less fluid. And if I had tilted it to the same degree, not a drop would have touched my lips, for the level of the liquid was lower the second time around.

PCT tells us that both times I flexed my muscles just enough to lift the cup, perceiving its weight. I directed it to my lips by controlling my perception of the direction of the cup and the position of my lips. And I tilted the cup controlling the perception of my lips to touch liquid. So, both times position, direction, coordination, and muscle movement were different. But I did control them. Therefor behavior is – as Powers stated – control of perception.

PCT, as an example of an alternative paradigm, in my opinion is the missing link in mental health care, a common starting point for treatment. It has one elegant explanation for all mental health issues: loss of control. And its repair mechanism is basically identical to its theory of personal growth, including learning: Powers called it Reorganization, because it’s nothing more or less than adjusting one’s own perceptual hierarchy to reduce chronic error and regain control.

The mental health care application of PCT is called MOL, Method of Levels.

Powers laid the groundwork for it; Tim Carey developed it to a workable model and also did tons of research to back up its effectiveness. His groundbreaking book Method of Levels in my opinion has the best subtitle in clinical literature: How to do psychotherapy without getting in the way. So immediately Carey places emphasis on the client. He’s the one who has to do the work.

MOL is more than Transdiagnostic, it’s a-diagnostic, which means that the therapist is not aware NOR interested in what bothers her client. She doesn’t analyse, diagnose, or advise, but just listens and asks, thereby providing the client with room to explore his problem to the fullest and generate his own workable solutions for it. It’s holism in its purest form.

By the way, none of this is new. What Carey did is basically cut the frills of all existing effective therapies and keep their core intact. This core, the effective element of all therapies, is maintaining the clients’ focus on the problem by reacting to external expressions of it. This to get the client to shift in point of view to evaluative, higher-level perspectives. All of this can be done by MOL-therapy, which looks a lot like Socratic dialogue. It is, in Careys own words, ‘simple, but not easy.’

MOL therapists report that they generally have a small number of short sessions before their clients feel a certain change and can go on with their lives.

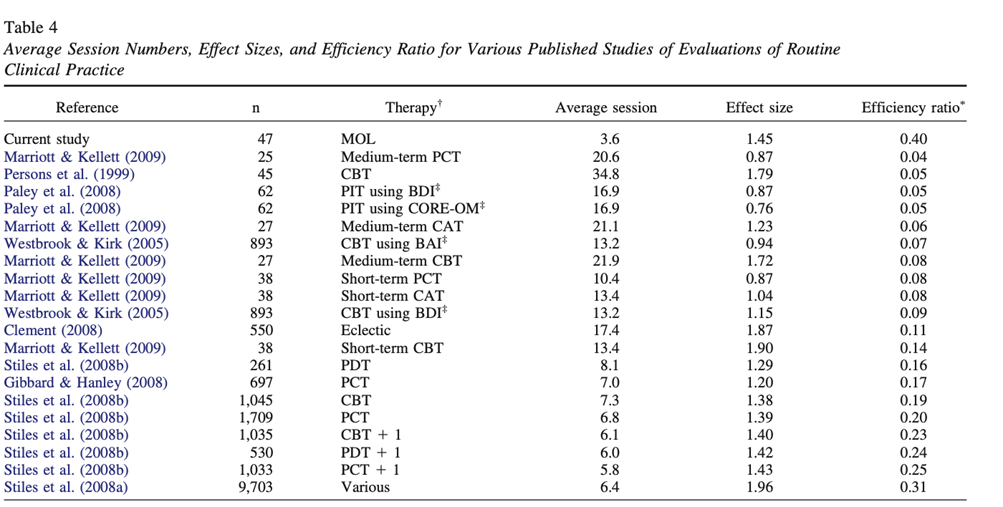

Carey theorized about this effectiveness and reported amazing results in small but a-select groups of participants, usually being the only acting therapist. This slide shows some of these quite remarkable claims. There is however a growing body of studies by an expanding number of researchers proving the applicability of MOL in many afflictions or ‘conflicts’ as PCT-people call them. I will not go into these studies, and I will not try to explain MOL here. Eva de Hullu yesterday gave a lecture about it, Pauline Tieleman will do so in a minute, and you can also read Carey or Rob Griffiths’ chapter in this book.

Expected gains

Applying the statistical evidence Carey et al. provided, I recalculated efficiency and efficacy of Dutch mental health care. For starters, most if not all administrative work can be skipped. One of the feats of not getting in the way is having an open online agenda in which clients can schedule their own meetings. This means the abandonment of no-shows, and much less paperwork. Furthermore, there is no diagnosis and no correspondence, resulting in very efficient use of the therapist’s time. So, instead of 40+% of time the MOL-therapist will probably spend less than 10% of her time not in direct contact with her client.

The remaining time is used far more efficiently, according to my summary of several published results. All in all, this saves 50 to 92% of the therapists’ time. This is not counting prolonged – and arguably useless – education in all sorts of methods, syndromes, and disorders, and intervision, supervision and so on. So, all in all, the gain will be even higher.

For the Dutch situation alone, the promise of MOL is that it will save 2 to well over 3,5 Billion euros per annum if we stop applying CBT and go full MOL. If you think this sounds too good to be true, I agree. We definitely need more proof. And therefor we need more research that’s not CBT or DSM-based. With this big a promise, it seems well worth spending a few hundred million on some trials. And just imagine the transnational budget we could invest!

Thesis available (in Dutch): https://www.gesprekkenmetgertjan.nl/methodsoflevels

Cambridge Photo by Vadim Sherbakov on Unsplash